Several years ago, Rebecca Fulleylove wrote a fantastic article quoting the inimitable French illustrator McBess;

"I wouldn't recommend trying to make it as an illustrator to anyone"

Matthieu Bessudo

Source: (itsnicethat.com)

It's interesting because this was written some time ago, and the perpetual angst of selling artwork continues. If we look at illustration as a commercial process, there is an eternal battle between the fulfilment of a project and the artist's freedom. This is a persistent pain among creators who are at odds between creativity for creativity's sake, freedom of expression, ideas and skills, and the real-world necessity to survive. To survive and earn, and to deliver for a customer.

Fundamentally a project in this sense is about what a client wants, and it follows that a compromise must be made. After all, could we imagine a world where projects are decided by creators and said to the customers!? - In the creative and marketing realm, this is necessary, as companies have rules, brands have images to uphold, with market positioning and messaging to portray. It's a fair argument to distinguish between an artist's and an illustrator's commercial intent.

While the world philosophises and meditates still on what it means to be an artist, progress soldiers on. Then along comes the ebb and flow of humanity's innovation. At the same time, we have had the dawn of sophisticated AI, defeating grandmasters at chess and 3d printing. I expect the means to conjure real-life paintings and products from the imagination in the next ten years. Perhaps it will not be too dissimilar to the replicator we grew up with on Star Trek. Command and the item shall miraculously appear. They say the best technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Perhaps illustration has gone the way of the victorian chimney sweep! The artist's mind, however, is here to stay. We might separate artists, artistic ability, commercials in illustration, and graphic design. While the image can now be handled with sophisticated tools, it still requires a graphic designer (for now!) with a keen eye for style and composition. An understanding of what "feels" correct. An AI might dream of articulating Zef.

Suppose we break down the feeling of correctness. In that case, we go down the rabbit hole of what beauty is, the golden section, and objective and natural beauty rules. People say art is subjective, but I would argue there are mathematical truths to what looks good; it is much more challenging to articulate why.

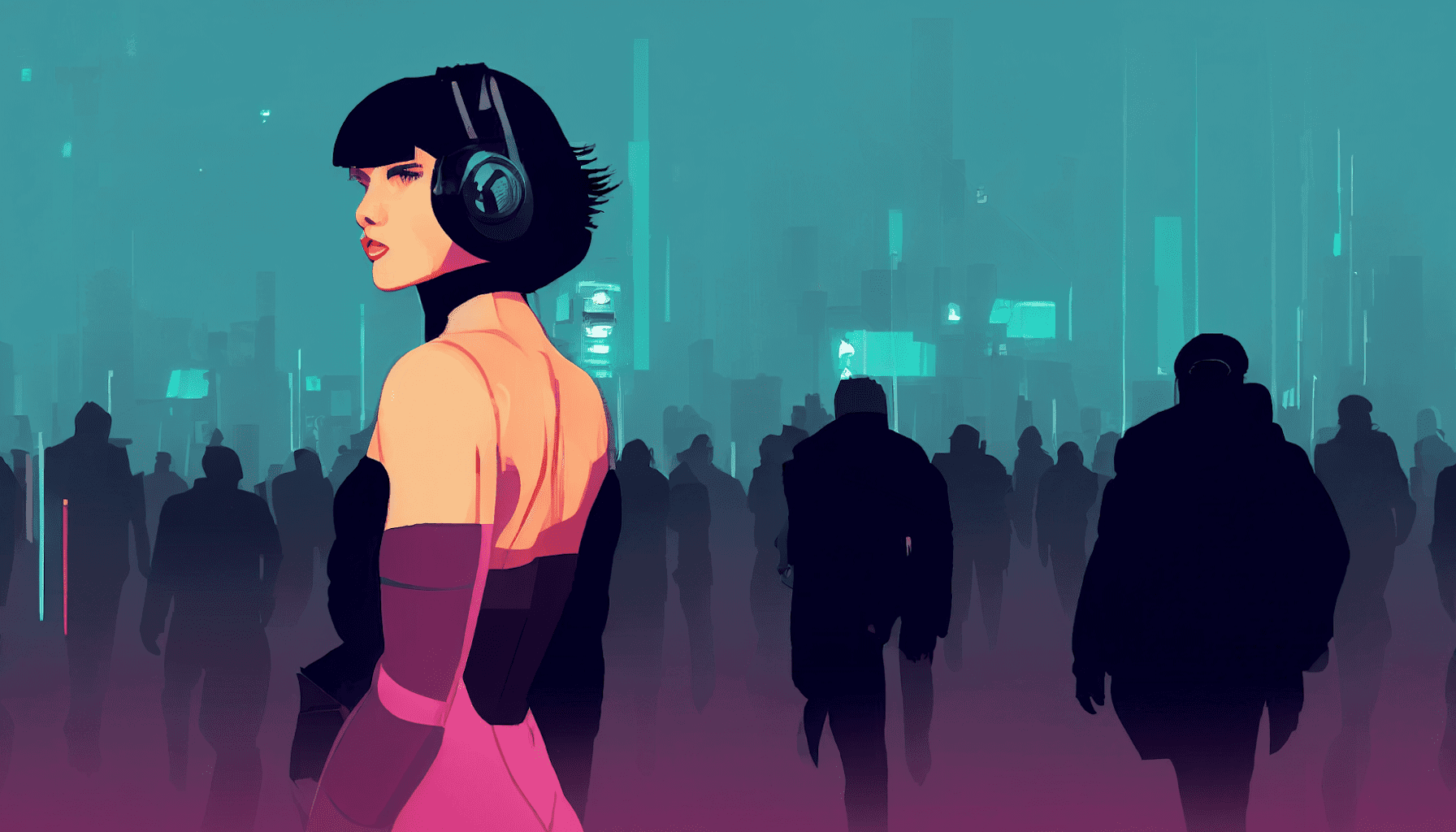

Now we can create anything relatively effortlessly, leveraging artificial intelligence toolkits such as Dall-e, Mid journey and StableDiffusion. Of course, the limitation comes back to the individual's knowledge of the subject matter and vocabulary. The ability to articulate what you mean and creatively say what you want from different perspectives for robots to understand. Does that mean bob the arborist becomes a masterful prompt engineer to produce very intricate and specific libraries of trees and plants? Hopefully yes. Experts on individual subjects could better express nuances in particular topics.

AI democratises art, expanding on creativity unbound from technical ability. While social media cries the lament of the technical artist, we still find value in the human touch, composition, tone, and understanding of emotion and mood. Further, it begs the question of originality, where I am hard pressed to find any artist living that does not stand on the shoulder of giants who came before. Maybe it is a twist or interpretation, but being completely new and unique, maybe not so much.

I think we underestimate how much these AI tools know. About everything. Yes, we can say everything, but what does that mean in terms of drawing a picture? Well, having all the knowledge digitally captured in humankind as a reference library would be helpful for starters.

If we break this down from more obvious encyclopedias, world history, objects and people. What if we focus on matters specific to creating images? Knowledge of paints and materials, textures, paper grade and quality. Material physics. The camera makes and models, lenses, vocabulary for framing composition, sweeps and pans. A complete history of all directors, artists, and photographers who lived alongside their life work.

Trying to explain an idea we conceive, we are bound by our limitations and experience. Our internal reference library has its finite boundaries. Rather than be defeatist, It's more productive to consider our limits and advantages and how we can leverage AI's superpowers to create better work.

While many digital ranchers will stick with horses when the proverbial automobile arrives, many more will harness innovation and special tools of the time for both creative and output advantages.

Even if the traditional painter baulks at using AI for a final painting. Breaking down the workflow of a new concept, from inception to first draft or moquette. We can progress to a few sample ideas and get approval. Imagine if Ai even takes over this stage and gives 500 iterations of a concept, saving weeks of manual effort.

"If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses."

Henry Ford

The problem isn't improving horses, as that does not cut the rancher out of the equation. However, when iterative improvement of technology is blown away by innovation, the rancher being no longer required sows unrest.

With all digital images ever captured to draw upon, and technical ability moot, the real existential crisis begs the question, can AI be more creative than us?

The illustrator is dead. Long live the illustrator.

Note: the illustrations for this post were generated with Mid journey AI.